by Ferne Arfin 16 May 2025

Almost secret London: The Guildhall Art Gallery

Inside and under London’s Guildhall

In the heart of the City of London, Britain’s historic financial centre, a cluster of ancient, modern and mid-20th century buildings wraps around a large public space that offers treats for art lovers and hides a Roman secret.

If you are a visitor perhaps you’ve heard of the Guildhall while reading about The City of London – often called The Square Mile – in a guidebook or on website. Maybe you’ve seen pictures of the glorious medieval building at its centre. But chances are, you’ve never visited.

Similarly, many Londonders have a vague idea that the Guildhall is in The City but would have difficulty telling you where it is or what exactly goes on there. I was among them. Last week, after living in ignorance for decades, I took myself over to see it (easy once you find it but not terribly easy to find), its art gallery and its hidden Roman amphitheatre.

Why “Almost Secret” London?

When I research travel, I often discover places that are relatively well known but nevertheless rarely visited. Visitors may have seen pictures or read about them in travel books but something or other discourages them from taking the next step and seeing them in person. They’re not “Hidden” or “Secret”, both popular travel writing labels. But they might as well be as they don’t get the attention or traveller footfall they deserve.

“Almost Secret” is a new feature highlighting some of these attractions, considering why they might be under-appreciated and explaining why they should be on your travel radar. I hope you’ll join me in finding surprises that are not “off the beaten path” but undiscovered right in the heart of things. Enter Almost Secret in the search box near the top right of all my pages to find more.

Explore this post

- Why “Almost Secret”?

- What is the Guildhall and what goes on there?

- Guildhall Yard and the Guildhall buildings

- The Guildhall Art Gallery

- The West Wing of the Guildhall

- The Guildhall

- A celebrated and infamous history

- St Lawrence Jewry

- The real secret of Guildhall Yard

- Who is Gilbert Scott?

- How to find the Guildhall

- More Almost Secret London Attractions

What is the Guildhall and what goes on there?

The Guildhall is the home of the Corporation of the City of London, its governing body. Often called “The Square Mile”, it’s the oldest part of London and a discrete, self-governing entity with its own rights and rules. Many of these date back to and are guaranteed by the Magna Carta. “The City” is not the London you, as a visitor, may think of when planning your trip to the British capital. It is short hand for Britain’s financial, banking and insurance centre in the same way that Wall Street is shorthand for that part of New York.

Now if this is already obvious to you, my apologies – just skip this section and continue below. But when I first arrived in London I had no idea about this and was confused to find that London and The City were not one and the same (Although sometimes they are. Confusing, see what I mean?). If you’d like to know more about this unique place and its arrangements, including the role of the Guildhall in its government , The City of London website explains it all very well.

Guildhall Yard and the Guildhall buildings

The Guildhall occupies a suite of buildings arranged around the vast plaza known as Guildhall Yard. Once filled with Georgian buildings the Yard was exposed when they were demolished in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Today a large public space, paved with patterned flagstones welcomes visitors and local worker. It also hides one of London’s almost secrets embedded in its surface – but you’ll have to read on to find out more about that.

Enter Guildhall Yard from the south entrance on King Street, ignore for the moment the glorious late Medieval building right in front of you and cross the yard to the right. The Guildhall Art Gallery, a modern gothic style building, sits on the east side of the yard.

The Guildhall Gallery, completed in 1999, occupies the East side of Guildhall Yard. The cloudless blue sky is a remarkable phenomenon for London.(photo ©Ferne Arfin May 2025)

The Guildhall Art Gallery

The Guildhall Art Gallery, faced with gleaming, pale Portland stone, houses the City of London’s art collection. Designed by architect Richard Gilbert Scott to replace a Victorian gallery destroyed in a 1941 German air raid, it opened to the public in 1999. The collection, begun in the late 17th century, includes more than 4,500 works of art – paintings, sculptures, ceramics and works on paper. Only a few hundred paintings are displayed at any one time, with the rest kept in storage elseware in the building.

The entrance hall is dominated by The Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibralter, 1782 by the Bostonian American artist, John Singleton Copley. The huge painting depicts what, from the European point of view, was the largest battle of the American Revolutionary War. It’s interesting because it’s a battle that is largely unknown by Americans, even those who are genuine aficionados of Revolutionary War history. It involved the French and Spanish fighting the British during a three year seige of Gibralter. The cost in loss of life and lost ships apparently influenced the terms of the Treaty of Paris that ended the war. In its day it must have been very significant and well known to Londoners because the painting, commissioned by the Corporation of the City of London, is seriously bigger than most private houses.

Because the Guildhall Art Gallery is “almost secret” it is one of the most peaceful public art galleries in London. On a sunny weekday at the start of London’s tourist season, there were no crowds to jostle for a better view. Instead the atmosphere was relaxed enough for friendly conversations about the art work to spring up spontaneously among gallery visitors.

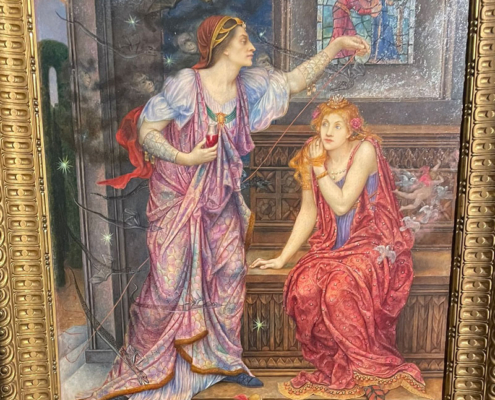

Commissions and aquisitions in the collection date back to 1670 and include works by Frans Hals, Joshua Reynolds, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Frederick Leighton and James Tissot. Between 150–175 paintings are displayed at any one time.

You can explore other works in the collection online or request to see specific works in storage by emailing the art gallery team at [email protected]. Include the works you would like to see and suggest two dates. Up to three people at a time can be accommodated.

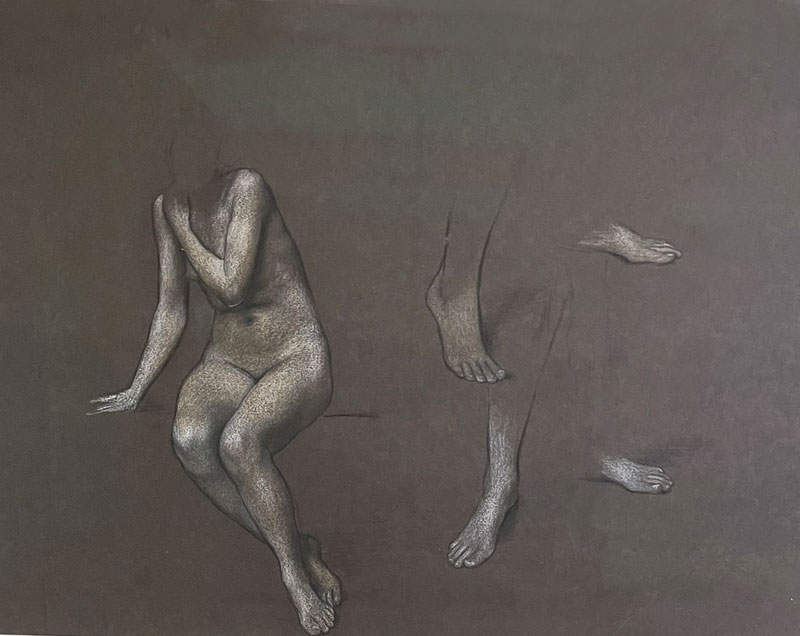

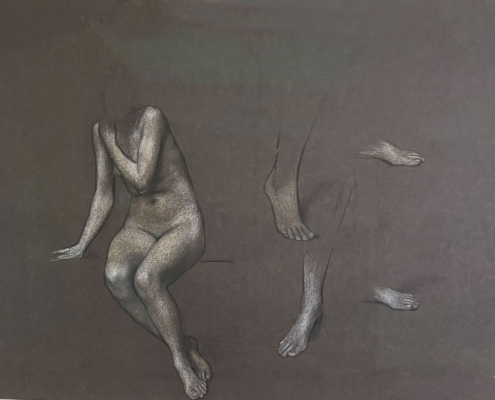

Below is a selection of the artworks on display when I visited in May 2025. Click on the thumbnail images for full pictures and details.

Because the Guildhall Art Gallery is “almost secret” it is one of the most peaceful public art galleries in London. On a sunny weekday at the start of London’s tourist season, with no crowds to jostle for a better view, atmosphere was relaxed enough for spontaneous, friendly conversations among gallery visitors.

The West Wing of the Guildhall

The West Wing was completed in 1975 and is typical of the heavy modernist style of much public architecture of the period.

The Guildhall

On the north side of Guildhall Yard,the medieval looking building pictured at the top of this page, is simply called The Guildhall and is one of the great survivors of the City of London. Records refer to a guildhall, a place where local guildmembers paid their taxes, as early as the 12th century. Most of the current building, including the Great Hall, dates from the early 1400s. But much of it has been rebuilt again and again.

The double hammerbeam ceiling of its Great Hall (also sometimes referred to as “The Guildhall” just to confuse you) was destroyed in the Great Fire of London (1666). It swept through London for five days and destroyed much of the old City of London within the ancient Roman walls. The hall was partly restored with a flat roof in 1670 and again in 1866, this time with a hammerbeam ceiling similar to the original.

The Guildhall, is used for ceremonial occasions such as the Lord Mayor’s Banquet. It is sometimes open tot he public on guided tours. photo by By Diliff – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alas that new roof didn’t survive the second Great Fire of London caused by the 29-30 December 1940 fire raid of Hitler’s Luftwaffe. Perhaps you’ve seen the famous picture of St Paul’s Cathedral surrounded by smoke and flames during the fires of that night. It’s likely some of that smoke came from the unlucky roof of the Great Hall going up in flames yet again. It was replaced in 1954 – without the hammerbeam ceiling – by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott.

A celebrated and infamous history

With its 27-meter-high vaulted ceiling, its carved Late Gothic stonework, its leaded windows and rows of guild-crested shields, the Great Hall probably hasn’t changed much in more than 500 years. As it has been since the early 1400s, it is still the setting for meetings of the Court of Common Council, the decision-making body of the City of London Corporation. What you probably won’t see today however, are the grim trials for treason and sedition that took place during the Tudor era and often ended in beheadings.

The ill-fated Lady Jane Grey, often known as the Nine Days Queen, was tried there before being executed at the Tower. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, was one of several Protestant martyrs, tried there for treason and, after conviction, burnt at the stake.

Today, the goings on at the Guildhall are considerably less bloody (we hope). You can see for yourself by visiting the Great Hall when the The Court of Common Council is in session. They meet nine times a year and a limited number of visitors, on guided tours, can witness their activities and see the hall. Find out about guided visits and book a tour with City of London Guides.

St Lawrence Jewry

As you enter Guildhall Yard from the south, facing the late Medieval Guildhall itself, the building immediately to your left in St Lawrence Jewry next Guildhall. It is considered one of Christopher Wren’s finest parish churches and was also, some say, the most expensive. Built between 1670 and 1677, it is a Guild church and the official church of the City of London Corporation. Like almost all the buildings in this part of London, it was badly damaged during the 1940 incendiary bombings of World War II.

Despite the damage, a small chapel was quickly created at the base of its tower to maintain the site as a place of worshop until the church could be fully restored. The church has a history of rising from the ashes. A house of worship occupied the site from at least 1136 but was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. It takes its name from the nearby Jewish business and residential district that existed here from 1066 until 1290 when King Edward I expelled the Jews from England. It was a familiar story throughout Europe. Kings needed to borrow money to finance their wars and Crusades. But Christians were not allowed to profit from lending money. So Jews (who were allowed to lend) were welcomed until the King found himself too heavily in debt. Then a trumped up charge (funny that word) was created as an excuse to expel entire communities.

Click on image below to toggle between views of St Lawrence Jewry

The real secret of Guildhall Yard

Walk into the centre of Guildhall Yard, between the 70s modernist, medieval, modern gothic and 17th century ecclesiastical buildings and you are actually standing at the heart of the largest amphitheatre in Roman Britain. All significant Roman cities and larger towns had amphitheatres so it makes sense that Londinium, the capital of Roman Britain, would have one. And more than likely, the largest one. But its location was hidden for centuries and buried under urban development for hundreds of years.

The remains of London’s Roman amphitheatre can be visited, free, on the lowest level of The Guildhall Art Gallery. Digital projections of the seating and some of the athletes and gladiators fill in the blanks. Drainage pipes are visible under a glass panel in the floor. According to Historic UK, some of the sand preserved in the ruins may actually have been the sand used to soak up blood on the floor of arena.

Archaeologists had been searching for it for at least 100 yeas when, in a surprise development, it was discovered during construction of the new Guildhall Art Gallery, in 1988. Roman Amphitheatres are usually found outside city or town walls or away from the main centres of population and trade. Unexpectedly for the archaeologists, London’s amphitheatre was found within the Roman walls.

The original structure was made of wood around 40AD. The theatre was rebuilt in stone in the 2nd century. It’s possible that substantial remains were still visible on the surface when the first Guildhall and house of worship were built on the edges of Guildhall Yard in the 12th century. Other than several rows of Georgian houses, demolished in the 20th century, no large structures were built here. The footprint of the Guildhall and the church of St Lawrence Jewry skirt the edges of the amphitheatre’s oval.

You can visit the remains of the amphitheatre free when the Guildhall Art Gallery is open. Just take the lift to the bottom level, then continue down the stairs to the lowest level of the building. But I think the best way to get a sense of the scale of the arena is to find the oval, more than 80 metres long, outlined in black stone near the perimeter of Guildhall Yard.

Red stars should help you spot the oval perimeter of the London Amphitheatre, indicated by the black stone inlaid into the surface Guildhall Yard. It passes the wall of St Lawrence Jewry, picture left and curves toward the West Wing of the Guildhall. In picture right, it curves around from the Guildhall Art Gallery toward the late Medieval Guildhall itself.

Who is Gilbert Scott?

You may have noticed the name Gilbert Scott popping up several times in this post and appearing frequently around London and the UK. Actually the question should be “Who are the Gilbert Scotts?” And the answer is a family (more like a dynasty) of architects who have influenced much of the look of London’s public buildings in the 19th and 20th centuries.

It began with the Gothic Revival architect Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811 – 1878). Among his designs – the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, St Pancras Station and hotel and St Mary Abbots Church on the corner of Kensington High Street and Kensington Church Street. It has the tallest spire in London at 278 feet tall.

His eldest son, George Gilbert Scott Jr. (1839 – 1897) worked in the Gothic Revival and Queen Anne styles, designing, among other things, buildings at three of Cambridge University’s college. Look for his work while touring there at Christ’s College, Pembroke College and Peterhouse. In London, he was behind the main buildings of Dulwich College in South London.

Next in the family business, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880 – 1960) , George Jr’s son, designed several buildings in Oxford and Cambridge Universities, Liverpool Cathedral and London’s majestic Battersea Power Station. But I’m guessing that for most visitors, his most familiar achievement was the truly iconic design of Britain’s red telephone box. He also replaced the ceiling of the Great Hall of the Guildhall after the 1940 firebombing of London of WWII.

Next in the family business, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880 – 1960) , George Jr’s son, designed several buildings in Oxford and Cambridge Universities, Liverpool Cathedral and London’s majestic Battersea Power Station. But I’m guessing that for most visitors, his most familiar achievement was the truly iconic design of Britain’s red telephone box. He also replaced the ceiling of the Great Hall of the Guildhall after the 1940 firebombing of London of WWII.

Richard Gilbert Scott (1923 -2017) Was the son of Sir Giles, he designed both the Guildhall Art Gallery and the West Wing of the Guildhall.

There are actually several more architects in the family who have designed churches and public buildings all over the world. You can find out more about them on their family blog GilbertScott.org, put together by the latest generation of the family.

How to find the Guildhall

The Guildhall is surrounded by limited access and one way roads, and cul de sacs. For the most interesting route, take public transportation to Mansion House Station (London Underground District or Circle Lines). A ten minute walk from there will take you through some of London’s oldest streets and lanes and past a few important landmarks.

- Leave Mansion House Station from the Queen Victoria Street exit. Cross at the lights.

- Enter Bow Lane, almost directly across from the station. Independent shops, cafes and pubs line this narrow, pedestrian lane. On your immediate right, pass St Mary Aldemary Church. The name indicates the oldest City of London church dedicated to Mary and its origins go back about 900 years. Destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, it was rebuilt by Christopher Wren later that century. Its uncharacteristic (for Wren) Gothic style may relate to the wishes if the congregation.

- Cross Watling Street, a short stretch of the original SE to NW Roman road that still runs from Dover to Shropshire and the Welsh border. Look left as you cross for a good view of Wren’s masterpiece, St Paul’s Cathedral.

- Continue to the end of Bow Lane where it meets Cheapside. On your left is another Wren Church, St Mary-le-Bow. Perhaps you’ve heard the saying that real London Cockneys were people born within the sound of Bow bells. That’s this church.

- Turn right on Cheapside and left at the pedestrian crossing into King Street. From there, you can see the late Medieval façade of the Guildhall. Continue down King Street and cross Gresham Street into Guildhall Yard.

An interesting aside

As you walk up King Street, notice Trump Street on your left. It’s been known by that name since at least the late 18th century. There are several theories about the origins of the name but since the theories disagree and contradict each other, they are not really worth sharing. Ironically, Trump Street leads to Russia Row. Today a mediocre office building with no redeeming aesthetic qualities occupies most of this short street.

As you walk up King Street, notice Trump Street on your left. It’s been known by that name since at least the late 18th century. There are several theories about the origins of the name but since the theories disagree and contradict each other, they are not really worth sharing. Ironically, Trump Street leads to Russia Row. Today a mediocre office building with no redeeming aesthetic qualities occupies most of this short street.

Manuel Harlan 2025

Manuel Harlan 2025