by Ferne Arfin 21 September 2020

Benedict Arnold – An American patriot in London?

To most people, his name is synonymous with traitor yet Benedict Arnold is memorialised in a lovely London church. What’s going on?

Why would anyone call Benedict Arnold an American patriot? Yet that’s how he’s described on a London historic marker. And at his final resting place, St Mary’s, Battersea a stained glass window and a marble headstone commemorate him. This pretty 18th-century church beside the Thames in southwest London is where Benedict Arnold, his second wife and his daughter are buried There, a stained glass window mentions the two nations he served uniting in friendship.

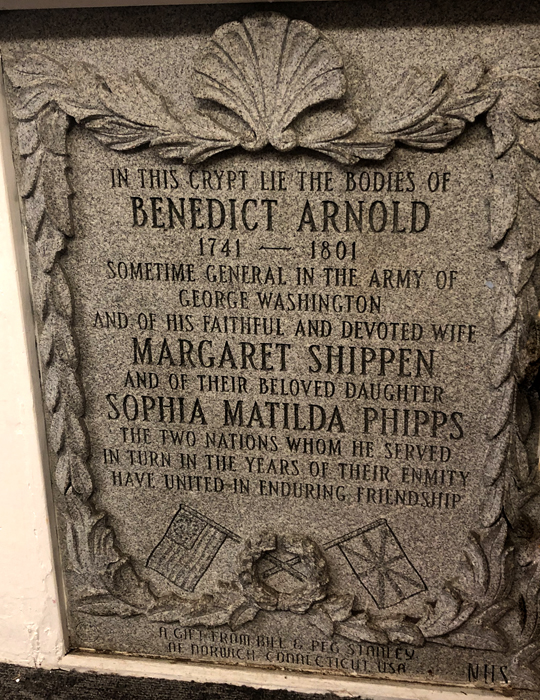

Below stairs in the crypt – now a bright, whitewashed basement kindergarten – a carved headstone in the wall (next to the children’s aquarium) marks the actual vault where Arnold and his family are buried. And a cast-iron plaque on a Georgian terraced house in tony Gloucester Place in Central London reads “Major General Benedict Arnold American Patriot Resided Here from 1796 until his death June 14, 1801”.

Seeing all this, without even a mention of his heinous treachery, you might be fooled into thinking that one of America’s greatest traitors is celebrated as a hero in Britain. Or that some international friendship organization is behind these memorials. But you’d be wrong on both counts.

Benedict who?

The final resting place of Benedict Arnold in the crypt of St Mary’s Battersea.

In fact, unless they are so interested in what they refer to as the “American War of Independence” that they’ve read extensively about it, most British people have never even heard of Arnold. And there are no mutual friendship and reconciliation societies that set out to celebrate America’s greatest Revolutionary War villain. Instead, all the architectural and funereal trimmings declaring Benedict Arnold an American patriot are down to several Americans who barely knew each other but who were fans of the infamous major general. This despite the fact that to most other Americans (even those who really have no idea who he was) his name is an epithet for traitor.

So, what exactly did he do?

George Washington appointed Arnold military governor of Philadelphia. There, he threw himself into a social scene that included wealthy Philadelphians and many British Loyalists. A widower with a taste for luxury, he met and married a much younger (19 to his 37), socially ambitious wife from a Loyalist (aka Tory) family. Major John André, a British spy, was her close family friend.

Nobody ever talks about whether George Washington was a good judge of character, but he certainly seems to have made a grave error in considering Benedict Arnold an American patriot. Arnold’s chequered background mixed acts of heroism with a record of argumentativeness, insubordination and attempts to resign from the military. By the time Washington appointed him commander of West Point he was heavily in debt and resentful about being passed over for promotion to a higher rank by Congress. And, he had an expensive young wife. Some believe she instigated his eventual act of treason.

So did he become a turncoat for money and sex? We’ll never really know but what we do know is that he accepted a promise of £10,000 and a higher rank in the British Army to turn over the plans for West Point to Major André. André was captured, tried and hanged. Arnold escaped but was paid only about £6,000 because his plot failed.

According to author Eric D, Lehman, who spent time reading Arnold’s letters for his book Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New London, Arnold completely switched sides, going beyond treason to fighting in attacks on Virginia and Connecticut.

Nobody likes a turncoat

Benedict Arnold and his wife moved to England but her dreams of high society were not realised. While he had some friends

St Mary’s Battersea, a Georgian church beside the Thames in London and burial place of Benedict Arnold.

amongst the 18th century Tories, most people found Arnold dishonourable and untrustworthy. He tried living as a merchant trader among the Loyalists in Canada but was so unpopular there that he was burned in effigy in front of his wife and daughter. Finally, they returned to London, where he spent the last five years of his life fighting trade disputes, lawsuits and a bloodless duel.

Even in death, Benedict Arnold could not return to his native Norwich, Connecticut, for burial in the family plot. In fact, his name was considered so evil that locals there defaced all the family graves except his mother’s. The sorry end, then, of Benedict Arnold an “American patriot”.

Benedict Arnold and St Mary’s Battersea

Arnold’s burial, in the crypt beneath St Mary’s Church in Battersea, would have remained an unremarkable bit of trivia if not for the late Bill Stanley, a former Connecticut state senator and founder, with his wife, of the Norwich Historical Society.

Stanley’s passion for protecting the legacy of Benedict Arnold’s military career prior to his 1779 treason was a lifelong obsession. A 2004 New York Times article reported that, as a schoolboy, in 1948, he was suspended for writing an essay claiming Arnold was the most valuable American who ever lived. When Stanley first visited St Mary’s and was shown the Arnold family grave – some lettering painted on the concrete wall of the crypt and hidden behind rubble – he was apparently moved to tears. He was fond of touting the traitor’s participation in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and the Battle of Saratoga. And, he was reported to have said of Arnold, “He saved America before he betrayed her” — which to my way of thinking is a bit like saying, he was a wonderful husband before he murdered his wife.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, he once told a reporter, “If we can forgive the Japanese for Pearl Harbor, can’t we forgive him?” That forgiveness took Stanley two decades of effort, and £15,000 of his own money, before he finally got permission to erect the gravestone now embedded in the wall of the St Mary’s basement.

About St Mary’s Battersea

St Mary’s is the oldest church in Battersea. The current Grade 1 listed building, dating from 1777, occupies a site that has had a church on it since Anglo Saxon times – the original church built in 800 AD. It is not a tourist attraction but a working parish church. As of this writing, it is open for socially-distanced worship and midday prayer services several times a week (see their website for the up-to-date schedule).

Staff at the church are friendly and welcoming. If you happen to visit when the church building is open – generally after services – and the basement kindergarten is not in session, someone may be able to show you Benedict Arnold’s grave in the crypt. Even if you’re not able to see the grave itself, it’s worth visiting St Mary’s for its classic Georgian architecture and its ancient and modern stained glass windows.

The windows are unusual in that none of them are on religious themes but, instead are secular and historical. The large east window was opened in a wall of the original Anglo Saxon church in 1379. The glass, which is painted rather than stained, was added in 1631 and was meant to emphasize the noble heritage of the then Lord of the Manor of Battersea, Sir John St John. It contains portraits of King Henry VII, his mother Margaret Beaufort, and Queen Elizabeth I.

In the mid 18th century, Earl Spencer bought the Lordship of the Manor of Battersea. With it came the responsibility of patronage of St Mary’s. Most of the rights and privileges associated with being Lord of the Manor are now ancient history, but Charles, Earl Spencer, the late Princess Diana’s brother, remains patron of the church. That gives him the right to appoint the vicar.

The modern windows

The four stained glass windows surrounding the apse were made by Kent artist John Hayward and added between 1976 and 1982. They are of famous men associated with St Mary’s in some way. The Benedict Arnold window, pictured above was (inexplicably) funded by an American donor, Vincent Lindnor of New Jersey. The other windows include:

- Artist JMW Turner who painted some of his river views from the Vestry window of the church. Turner then lived anonymously as Mr.Booth, at 119 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, across the river from St Mary’s. The house can just be seen from the churchyard.

- Poet William Blake, who was married at St Mary’s

- 18th-century botanist William Curtis who, as a member of the Society of Apothecaries, was director of their garden, now known as the Chelsea Physic Garden (and open to visitors). He is known for his book Flora Londinensis, a catalogue of all the plants then known to be native to London. Many of his samples were collected in the churchyard of St Mary’s where he is now buried.

A riverside walk and cruise to St Mary’s

The best way to get to St Mary’s is by walking along the Battersea side of the Thames. Combine that with a river cruise on one of London’s many commuter boats and you get a glimpse of West London life that is off the beaten path but makes a fine family day out. Along the way, you’ll see many of the developments that are changing the London skyline, several interesting communities of river dwellers in London’s residential barges and the river traffic of working boats, tourist cruises and London’s river commuter boats.

Albert Bridge, start of Riverside Walk.

Hop on a river bus at any north of the Thames piers in central London and get off at Cadogan pier for a good close up view of Albert Bridge. Pass the bridge, heading west and cross the Thames on Battersea Bridge. It’s the next bridge along, by the statue of James Whistler, who lived nearby.

On the Battersea side, turn right onto the brick-paved pedestrian path and continue heading west. The river is on your right and riverside residential developments are on your left. St Mary’s Church is about ten minutes along. It’s an oasis of Georgian architecture surrounded by steel and glass king-of-the-universe blocks of flats. From the front garden, you can see views painted by Turner and, if you are sharp-eyed, you might see his final home on Cheyne Walk, across the river.

If you’re hungry, consider turning left just past the church and immediately right onto Battersea Church Road. It leads into Battersea Square, a few hundred yards along. Gordon Ramsay’s gastropub, London House, is on the square and a good family choice. Kids 12 and younger eat free from the children’s menu, all day, every day (one child per one adult choosing from the a la carte menu). You’ll need to book ahead.

If you continue west out of the square, you can rejoin the river walk by crossing Vicarage Gardens, on your right. Continue west, with a short detour around the London Heliport, to Plantation Wharf where, after admiring the houseboats and residential bargest, you can catch the RB6 riverboat to Putney Bridge Pier for the London Underground, or for the eastbound cruise back to Central London.

And those other eccentrics

Two other Americans spent time and money honouring America’s earliest and greatest traitor Benedict Arnold. Peter Arnold, a private citizen living east of London, applied to English Heritage in 1984 for funding to place one of their blue historic plaques on a building in Marylebone where Arnold lived out his last years. Peter Arnold could be a distant relation of Benedict but their branches of Arnolds separated about 150 years before Benedict Arnold was born.

At any rate, they turned him down. Three years later he applied for planning permission from Westminster City Council and installed a black marker on the house at his own expense. It bears the words “Major General Benedict Arnold American Patriot Resided Here From 1796 Until His Death June 14 1801” – no punctuation and no mention of the real reason Arnold is infamous.

Another American, a Vincent Lindner of New Jersey paid for the stained glass window at St Mary’s Battersea. Since he died in 2009, we can’t ask him why.

Ferne Arfin 2015

Ferne Arfin 2015 Ferne Arfin 2020

Ferne Arfin 2020

I am a Benedict Arnold descendant, that is of Governor Benedict Arnold of Rhode Island, namesake and great grandfather of the General. Perhaps General Arnold was only ever acting in the nature of his ancestor captain John Marchant, and so many other good Anglo Saxons who have conquered the world. Marchant teamed up with Sir Francis Drake and went on a seafaring jaunt in which they invaded Spain at Cadiz, and later was killed while attacking the Spaniards in Panama. General Arnold’s ambition and pride got ahead of him. Such is history, and English blood.

With no words of forgiveness, I do have words of recognition of his exploits and to our history for his contributions at the battles fought at Ft. Ticonderoga and Saratoga. The nation of the United States was founded on the backs of many conflicted people including Arnold who now pays the price for his acts withering out of sight in a place leaving him lost in a basement to be found only by the few citizens who wondered what happened to him to find him. Perhaps it’s better a place be found for he and his family in the United States where the full story of the nation’s conflicted founders can be told and his acts of treason fully revealed as to why the name Arnold is synonymous with the word traitor.