by Ferne Arfin 7 June 2023

Discovering Aisne

Out of the shadows at last for this secret corner of France

Art Deco architecture with a Flemish twist in Saint-Quentin ©FX.Dessirier/Agence Aisne Tourism

Last month I spent a few days discovering Aisne in Northern France.

“Where?” I hear you ask. Don’t be embarrassed by your ignorance of French geography. When I checked into my Parisian hotel at the end of the visit to Aisne, the Parisian concierge asked the same thing. And Paris is just an hour and a half away by train. As I discovered, a lot of French people haven’t heard of Aisne either.

What’s odd is that Aisne, in the Hauts-de-France region of northern France, isn’t a new départment. It wasn’t created during a 20th-century reorganization of local government. It’s been around since départments were originally created in the late 18th century.

Perhaps it’s been overshadowed by the famous neighbours that surround it – Pas de Calais, Champagne, Somme and the Belgian border. It’s not as though it hasn’t produced its share of famous sons. Alexandre Dumas (The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo), Racine and the fabulist, Jean de la Fontaine, all hailed from Aisne. The river Somme rises in Fonsommes, near Saint-Quentin, Aisne’s largest city. And it was here that the horror of WWI, trench warfare, was first practised, during the Battle of Aisne in 1914.

Now this primarily rural region is ready to show off its treasures – impressive cathedrals, walled towns, fortified churches – to more international visitors. And, the good news is, it’s quite good value for rail and road travellers.

The town that rose like the Phoenix – again and again

The largest city in Aisne (traditionally part of Picardy), Saint-Quentin was long known for its textile industries, producing wool in the Middle Ages and linen products through the 19th century. Its strategic position, between the rich farmland of the Champagne region, with its annual fairs, and Flanders, to the east, made it an important trading centre in the Middle Ages.

But hundreds of years of serial wars and plagues took their toll. The endless wars between England and France in the 14th century (the Hundred Years War) were followed by the wars between the Dukes of Burgundy and the King of France in the 15th century, battles with the Spanish (who controlled the Netherlands) in the 16th century and the religious wars and plagues of the mid 17th century. The 19th century was no better, seeing Saint-Quentin occupied by the Russian Army and later falling to the Prussians in the Franco-Prussian War. It is a testament to the resilience of the locals that so many landmarks of these earlier periods remain – restored or rebuilt again and again.

Saint-Quentin – an Art Deco showcase by default

Perhaps none of this history was as ultimately destructive as World War I. Before the war was over, 80 per cent of the town’s buildings had been damaged or destroyed.

Remarkably, that gave this community yet another opportunity to do what it seems to do best – recoup and rebuild. This time, so much of the ordinary fabric of the town was destroyed that the painstaking reconstruction of Flemish Gothic and 19th century Neo-Gothic buildings was not immediately practical (though several were later repaired and are among Saint-Quentin’s major landmarks). But in the period between the war, the practical mode of the day was Art Deco.

The style is everywhere, from the facades of buildings along the main shopping street, Rue de la Sellerie, to the fittings and decor of the Municipal Council Chamber. Some Art Deco sites in the town are standouts – notably the train station and the station buffet (check out the photo gallery below). But most Art Deco clues are so woven into the quotidian, that unless you are an expert yourself, you’ll probably need a guide to help you spot them. Look for the floral abstractions in the wrought iron railings and window grilles. Get out your binoculars to study the frieze on the former Nouvelles Galeries department store. What looks at first to be typical Art Nouveau panels, covered in bunches of grapes and trailing vines, is actually a bas-relief of abstract shapes and machine-made objects – very “between the wars”.

Art Deco in Saint-Quentin

Click each image for best view

While you’re there…

Saint-Quentin is not just about Art Deco monuments and landmarks. The town has more than enough to keep you busy on a short break or an overnight stop on a road trip through the area. Here are some of the highlights.

Hôtel de Ville

Saint-Quentin’s Hôtel de Ville, or town hall, is an example of the “Flamboyant” Gothic style of the late Middle Ages. It was completed in 1509 though work began as early as the 14th century. Like much of the town, it was heavily damaged during WWI, but its exterior was extensively restored over a period of 25 years. The interior bears the influence of 1920s and 1930s Art Deco and some of these rooms can be visited on tours scheduled by the tourist office.

The exterior is totally late Gothic and decorated with statues and carved animal figures on every available space. At least 170 sculptures and statues are mounted on and around the facade. They include political symbols, familiar animals and the fantastical creatures of a Medieval bestiary, scenes of daily life, angels, and musicians. The facade has been described as a book in stone.

A campanile added in the 17th century holds a carillon of 37 bells. Every quarter of an hour is marked by a peal of the bells but the carillon is actually a true musical instrument capable of being used to play a wide variety of tunes. Carillon concerts are held occasionally.

Saint-Quentin’s Hôtel de Ville in front of the town’s main square. Unlike Arras, where the town’s grandest square, in front of its Gothic city hall, is where its weekly market is held, Saint-Quentin’s markets are held in a smaller series of streets behind this building.© Sylvain Cambon / Agence Aisne Tourisme

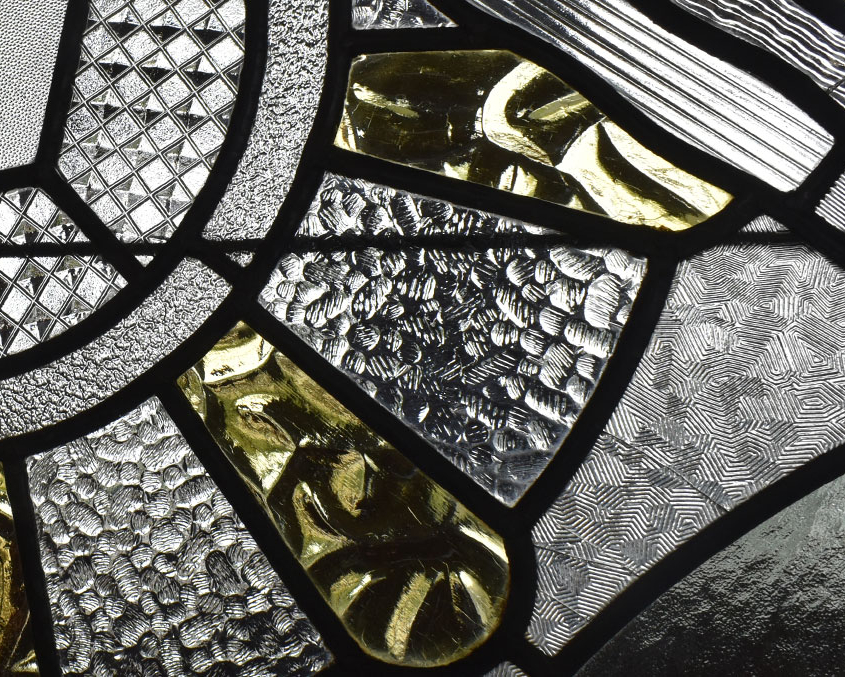

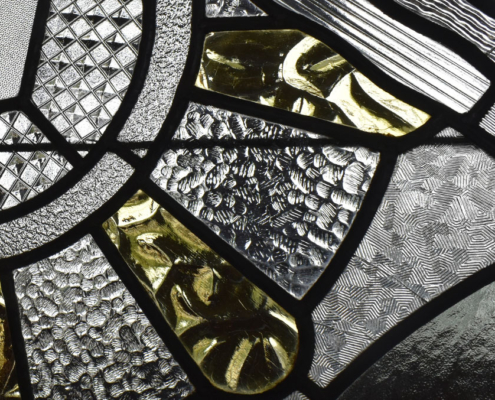

By far the most impressive building in Saint-Quentin is the Basilica. In fact, it is the second largest religious structure in Picardy after Amiens Cathedral. And although it looks as impressive as a cathedral it never was one. It was created between the 12th and 15th centuries at the site of the martyrdom and burial of the Gallo-Roman Quentin. The site was a magnet for pilgrims from the 9th century onward and ultimately became a collegial church with a chapter of canons in the 11th century. Parts of its crypt are at least that old. The empty sarcophagus in the crypt purports to be the one in which the saint was buried after being exhumed in the 4th century. So a lot of fascinating history attaches to this place. The building itself tells many different stories. The gleaming white west front, which is now the main entrance to the church, is the oldest part – about 900 years old and was the original belfry. Fire destroyed the top of the west front, but the canons were able to replace it with help from King Louis XIV, the Sun King. It is well worth booking a tour to enter the ancient crypt, to see the impressive stained glass windows (some date from the 12th century and some are Art Deco replacements) and learn more about the church’s history.

The Basilica has many stories to tell and is definitely worth a guided visit. Pierre Poschadel/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

Worth a side trip

If you are interested in the social reformers and Utopian experiments of the 19th century, you may want to visit the Familistère de Guise, about half an hour’s drive from Saint-Quentin. This so-called “social palace”, devised by August Godin, was a self-contained worker’s community where employees of the Godin cast iron foundry lived, worked, sent their children to school and enjoyed educational entertainments all under a benevolent if somewhat paternalistic regime. Like a lot of Utopian plans, the factory outlived the social engineering and is still making cast iron stoves today. Visiting is more of an educational experience than a holiday or vacation outing but interesting nontheless. I’ll be writing more about it in a future post, with pictures.

Art Deco stained glass window in this ancient cathedral is one of several added to the church to replace windows destroyed in WWI. Several of the original 12th century windows somehow survived. Photo by Patrick, Creative Commons

For more information and to book a tour, visit the Office de tourisme du Saint-Quentinois, 3 rue Emile Zola, 02100 Saint Quentin, [email protected]

Saint-Quentin’s art museum is located in a small, elegant pavilion-style building across from a school in a residential neighbourhood. Antoine Lécuyer was King Louis XV’s court portraitist – and his output, in pastel portraits, is as remarkable a record of the French king as Holbein’s pencil portraits were of the court of Henry VIII. The heart of this museum is a collection of 100 pastel portraits. The museum also holds 17th-century Italian and Scandinavian paintings and French paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Between 1923 and 1981, Motobecane made two-wheeled vehicles – bicycles, motorbikes, scooters and motorcycles. The brand was acquired by Yamaha and is now made in Taiwan, And the Motobecane factory has a new life as the Village of Old Trades and Motobecane Museum. A collection of period shop fronts, dating from the mid-19th century to the 1950s, is staffed by costumed, volunteer interpreters. They’re knowledgeable about the crafts and trades practised in a typical working village. At the heart of the “village”, a collection of vintage Motobecane bikes and cycles will entertain any young “petrol head” or two-wheeler collectors in your party.

Ferne Arfin 2023

Ferne Arfin 2023 Ferne Arfin 2023

Ferne Arfin 2023

Leave a Comment

What do you think?Please add your comments and suggestions here.